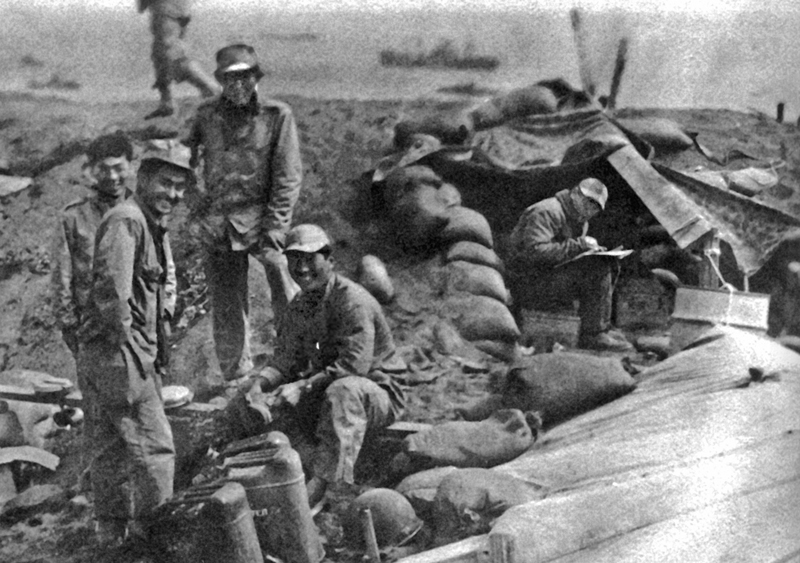

Above: IWO JIMA, February 23, 1945: The flag-raising atop Mount Suribachi became the symbol of the war in the Pacific. The marines from Easy Company, 28th Marine Regiment, raised a small flag when they took Suribachi earlier that day, but the battalion commander ordered a larger one erected. When AP photographer Joe Rosenthal shot the second flag-raising, at least two MIS nisei were among the U.S. troops near the summit. They were among more than 50 MIS nisei who served with the marines on Iwo Jima. Many deployed from the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area (JICPOA) in Hawaiʻi. Until late in the war, MIS nisei assigned to JICPOA worked at an annex in a former furniture store on Kapiʻolani Boulevard. The Navy and Marine Corps needed their skills, but didn’t allow Japanese Americans in Pearl Harbor. National Archives photo.

As 1945 dawned, the Allies were on offense everywhere against Imperial Japan. MacArthur’s forces were mopping up in the Philippines. Long-range U.S. bombers were pounding Japan from bases in the Marianas.

Iwo Jima

In February 1945, U.S. marines landed on Iwo Jima, a small volcanic island that would provide a haven for damaged B-29s and a base for their fighter escorts. MIS teams were with each of the three marine divisions. In the war’s bloodiest fighting to that point, the United States suffered 26,000 casualties, including 6,800 killed; the 20,000 Japanese defenders were wiped out, with the exception of 1,000 who were captured or surrendered, many thanks to the MIS nisei.

Okinawa

Okinawa came next. The battle there began on April 1, 1945, with the largest amphibious landing of the war in the Pacific. Months of vicious fighting killed about a quarter-million people, including 12,500 Americans, more than 100,000 Japanese troops and conscripts, and 140,000 Okinawan civilians – one third of the island’s population. Hundreds of MIS language specialists were deployed for this climactic battle. So great was the demand that nearly 200 nisei were pulled out of basic training in Hawaiʻi and sent directly into the battle. Some 36,000 Americans were wounded on Okinawa, and an additional 33,000 were non-battle casualties, many of them psychiatric.

Many other nisei linguists continued to serve in Guam, the Philippines, China, Burma and dozens of Pacific outposts, everywhere they were needed against a stubborn enemy.

Still others were preparing for Operation Olympic, a massive invasion of Kyushu scheduled for November. And planning had begun for Operation Coronet, the invasion of the Kanto Plain the following spring.

On August 13, 1945, a team of 10 MIS nisei bound for the pre-Olympic invasion staging with the 11th Airborne Division died in a plane crash on Okinawa. The airfield had been obscured by smoke laid down to foil a Japanese air raid. Japan’s surrender was announced two days later.

Looking Like The Enemy

On Okinawa, an MIS nisei from Hawaiʻi was separated from his unit and wound up in a bomb crater between U.S. and Japanese positions: “Every time I stuck my head up, both sides would shoot at me. I had a Japanese face and an American uniform.”

Next: Intelligence Coups