Above: PEARL HARBOR, December 7, 1941, Sunday morning, U.S. Navy ships attacked by Imperial Japanese Navy carrier aircraft. U.S. Navy photo.

Europe and Asia were already aflame, and many wondered how long America could remain neutral. Yet Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on O‘ahu shocked the 423,000 civilians and 50,000 military personnel in the Islands and thousands more on ships.

There was no time for inaction. Military personnel were ordered to report to their duty stations. More than 2,300 U.S. sailors, soldiers and marines died that day. Estimates of civilian deaths range from 48 to 68, almost all of them caused by wildly fired U.S. anti-aircraft shells. By the afternoon of December 7, martial law had been imposed on the Territory and would continue for three years.

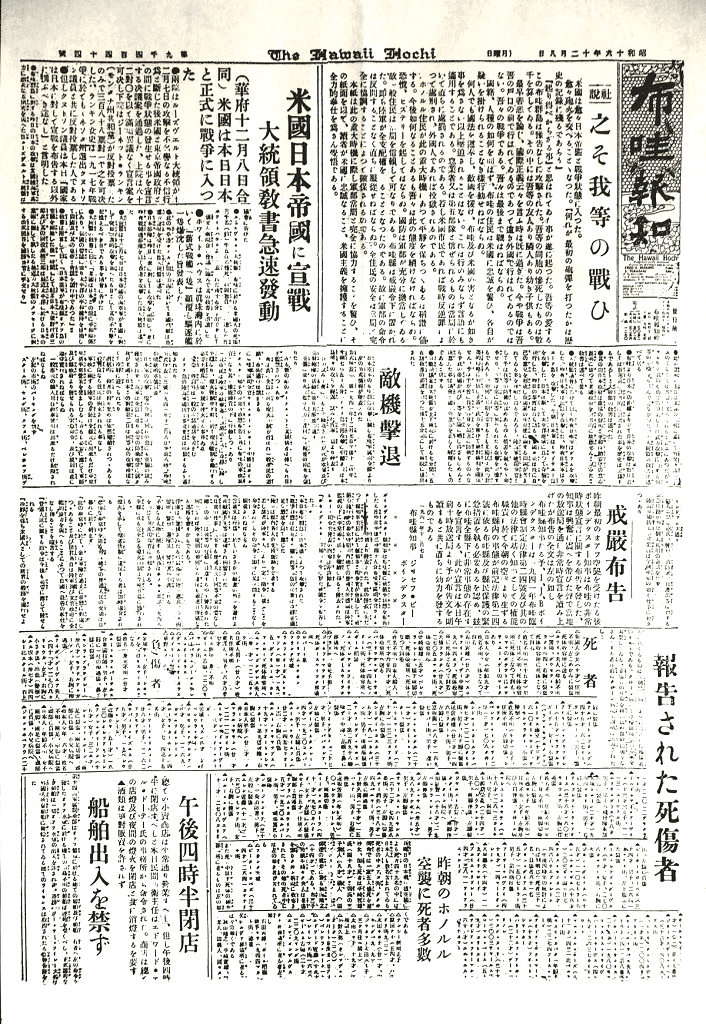

“This is Our War”

The day after Japan attacked Hawaiʻi, the Hawaii Hochi, Hawaiʻi’s leading Japanese language newspaper, published “This is Our War” an editorial encouraging loyalty to the United States. Fred Kinzaburo Makino founded the Hawaii Hochi in 1912 to campaign for social justice, and he was an early critic of Japanese imperialism. Shortly after the attack and declaration of martial law in Hawaiʻi military authorities closed the Hochi and other Japanese language papers. They were later allowed to resume publication, but under censorship.

Translation* of the Hawaii Hochi editorial:

THIS IS OUR WAR

America is now at war against Japan. We are now engaged in the exchange of destructive explosives. Whoever fired the first weapon will be recorded in history. “The thing that should never happen” has happened. The Hawaiian Islands which we love dearly have been attacked without warning. Our fellow citizens in the thousands have perished. Among them are friends, neighbors and even children.

Gone is the time to debate international laws and the right or wrong of international relations. Already war is at our doorsteps, not at distant foreign lands. It is our war. We must fight to the end.

The citizenry of Hawai‘i must collectively endeavor to serve our country by disregarding ethnic differences and avoiding behaviors that cast doubts against ourselves.

We must all uphold our constitution, and, as long as we do not engage in activities contrary to our national security, we should never be subjected to any oppression. This applies not only to our actions but to our spoken words as well. Violators will be duly punished — if a U.S. citizen, he will be punished; if a foreigner, he will be imprisoned.

Honolulu residents will receive words of praise for good behavior and loyal support of the national efforts during the war crisis.

Hereafter, we must maintain this loyalty under all circumstances. We must never panic or display any mass hysteria.

Our national defense is under total control of our defense agency so that the entire citizenry may thusly rest assured. Hawai‘i has been placed under the rule of a military governor. Therefore, we must all abide by the rules and regulations established by the military. The safety of all residents will be overseen by the military.

It is the aim of this publisher to fully cooperate and support the military governor and, thusly, urge all Hawai‘i residents to endeavor likewise throughout the war.

Fred Kinzaburo Makino

Founder and Publisher

The Hawaii Hochi

* Hochi editorial translation by MIS veteran Herbert K. Yanamura

Fear & Rumors

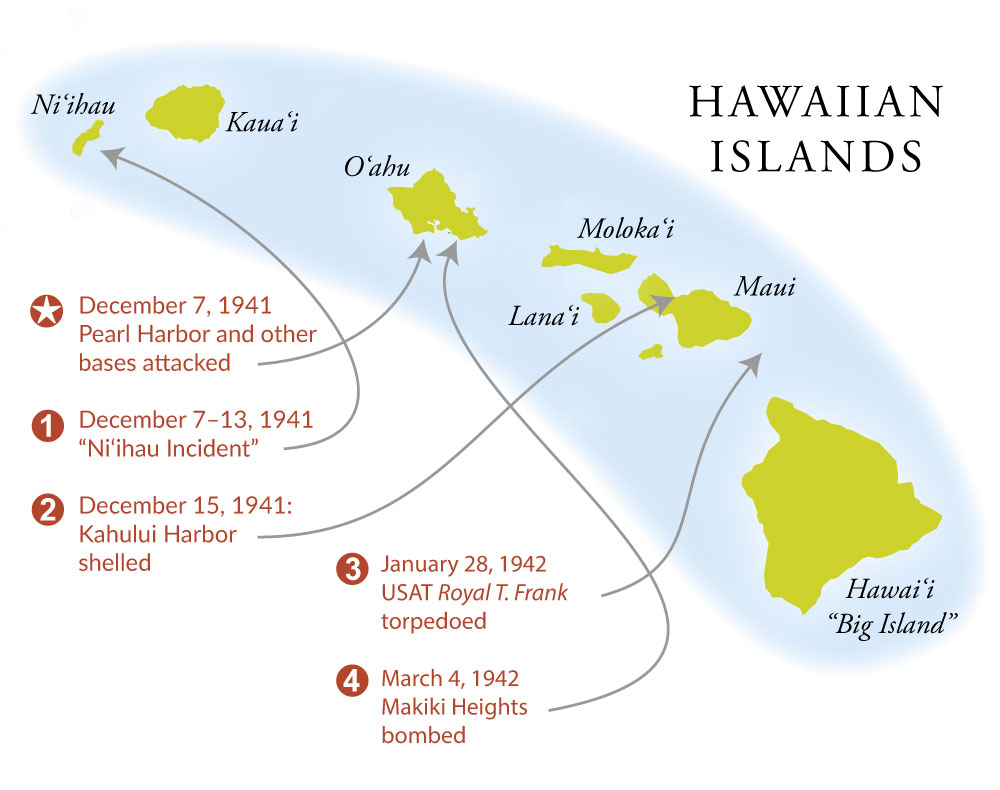

Fanning fears of invasion and racial hysteria, Japanese forays against Hawai‘i continued for months.

1. December 7–13, 1941: A Japanese pilot crash-landed on Niʻihau on the 7th, was captured, then briefly gained control of the isolated island with coerced help from two of the three resident Japanese. The pilot was overcome and killed by Ben and Ella Kanahele. One of his helpers committed suicide and is still cited by some racists today as an example of AJA treachery.

2. December 15, 1941: A Japanese submarine surfaced off Maui’s Kahului Harbor near dusk and fired some rounds from its deck gun at pierside facilities, causing minor damage to the Maui Pineapple Cannery. Subs also shelled Kahului, Hilo and Nawiliwili harbors with little effect on the moonlit night of December 30-31. Other enemy sub sightings were reported through January 1942.

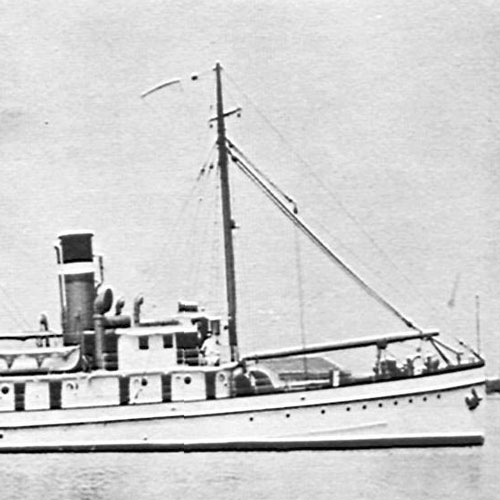

3. January 28, 1942: A Japanese submarine torpedoed and sank the U.S. Army Transport Ship (USAT) Royal T. Frank about 7 a.m. between the Big Island and Maui, killing 24 of the 60 people aboard. Twelve of the dead were nisei draftees who had just completed basic training. Eight AJAs who survived the sinking went on to serve with the 100th “Purple Heart” Battalion in Europe.

4. March 4, 1942: About 2 a.m., a few bombs from a Japanese flying boat fell on Makiki Heights on Oʻahu, causing little damage.

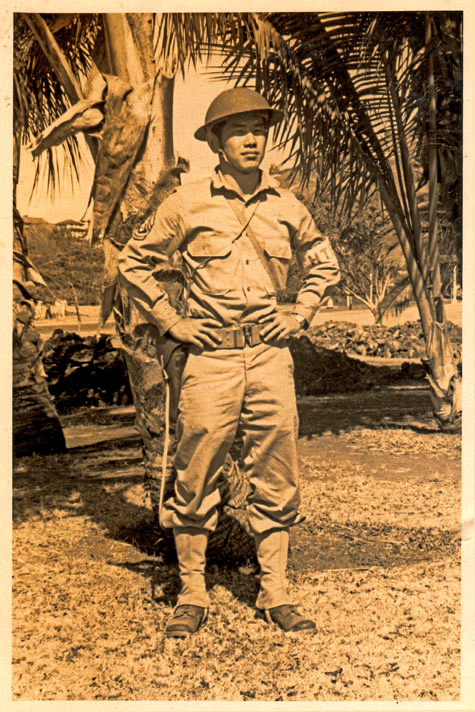

Territorial Guard Dismisses Nisei

More than 300 University of Hawai‘i ROTC cadets – most of them Japanese Americans – were called to active duty on December 7 as members of the Hawai‘i Territorial Guard, supporting the 298th and 299th Infantry Regiments in guarding against possible invasion. On January 19, 1942, however, those members of the Territorial Guard who were Japanese were abruptly dismissed. Once they got over their shock and outrage, 169 of the forsaken nisei organized themselves into the Varsity Victory Volunteers, serving as a labor battalion until they were allowed later to enlist in the MIS or 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

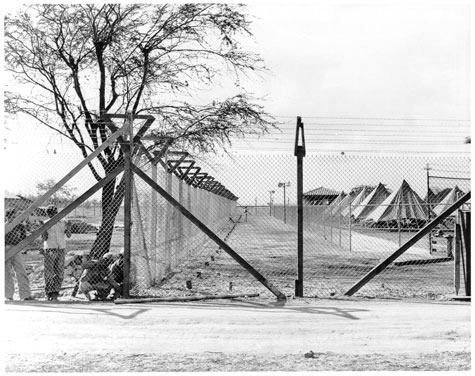

Internment & Hawai‘i

High officials in Washington and some in Hawai‘i wanted to remove all ethnic Japanese from the islands despite the support of many local leaders and authorities who noted the absence of disloyal acts. Unlike the West Coast, local leaders and Army commanders built prewar bonds of mutual trust and operated on a principle of inclusion. Mass removal or relocation would have crippled Hawai‘i and overwhelmed available shipping. Ultimately, about 1,000 Japanese community leaders, including priests and educators and nearly as many dependents were interned, most on the Mainland, some at Honouliuli and other local camps.

Next: On the Move