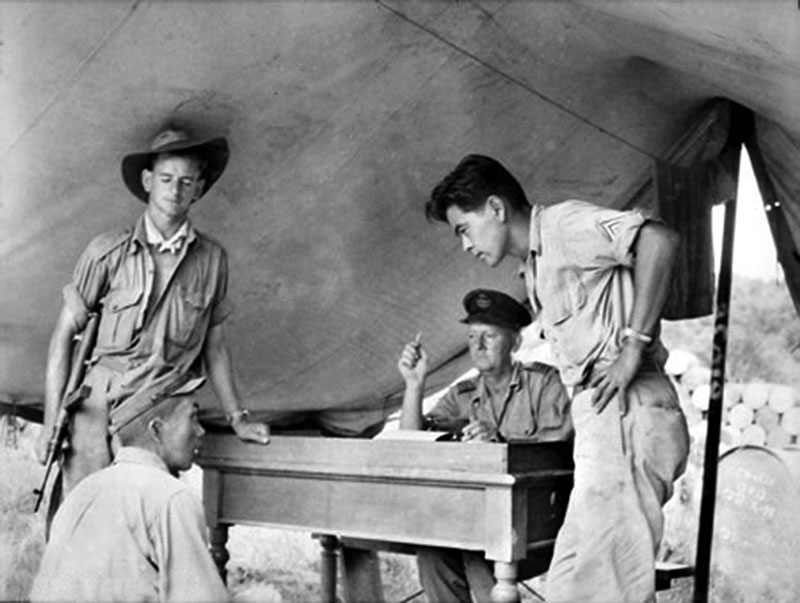

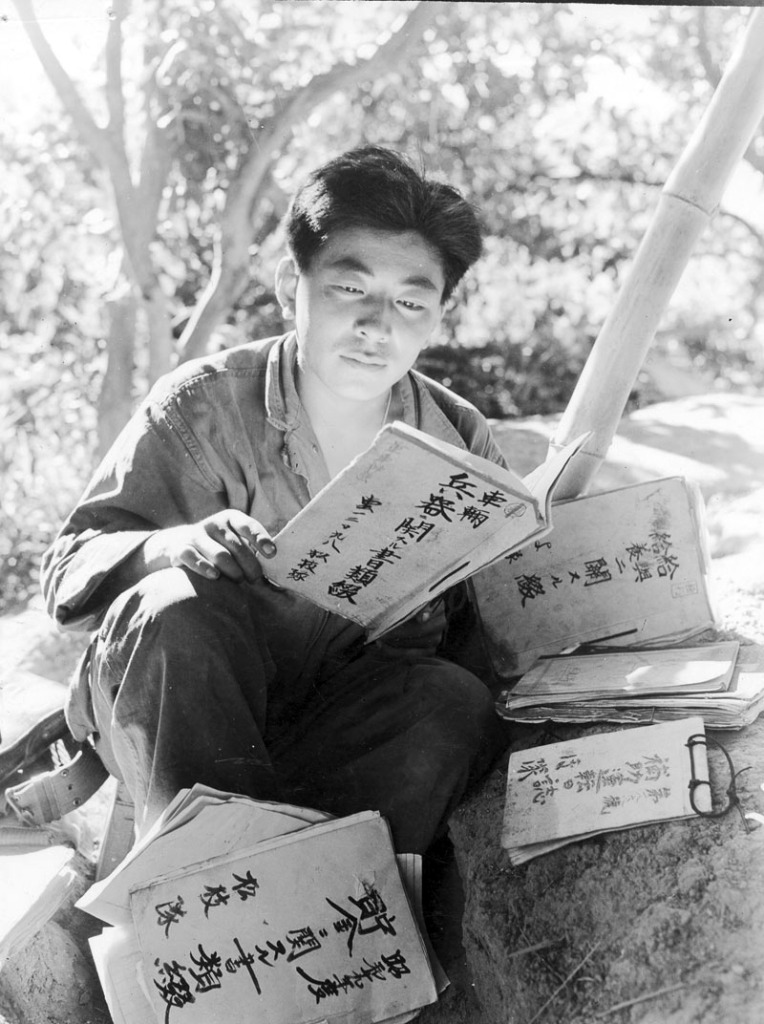

Above: AITAPE, NEW GUINEA, April 22, 1944: Japanese prisoners, left, answer questions from Military Intelligence Service language specialists Harry Fukuhara, right, who volunteered from the Gila River Internment Camp in Arizona, and Shoji Ishii, of San Francisco. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo.

The first Americans of Japanese ancestry to see combat in World War II were military intelligence specialists in the Pacific.

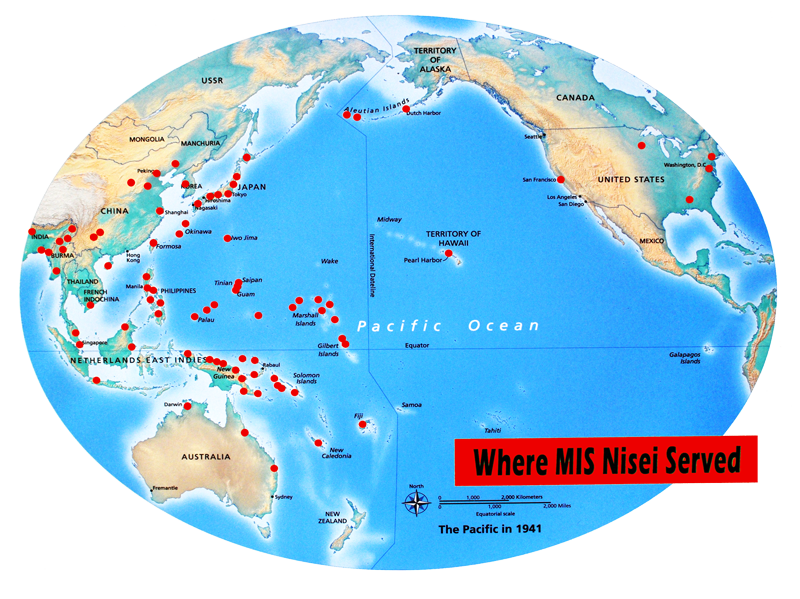

The MIS nisei did not serve together as a unit like their brothers in the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team did in Europe. MIS soldiers served in ones and twos, in 10-man teams, or detachments with the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Allied units, all over the Pacific and China-Burma-India theaters of war. Their assignments were often temporary and undocumented. They served:

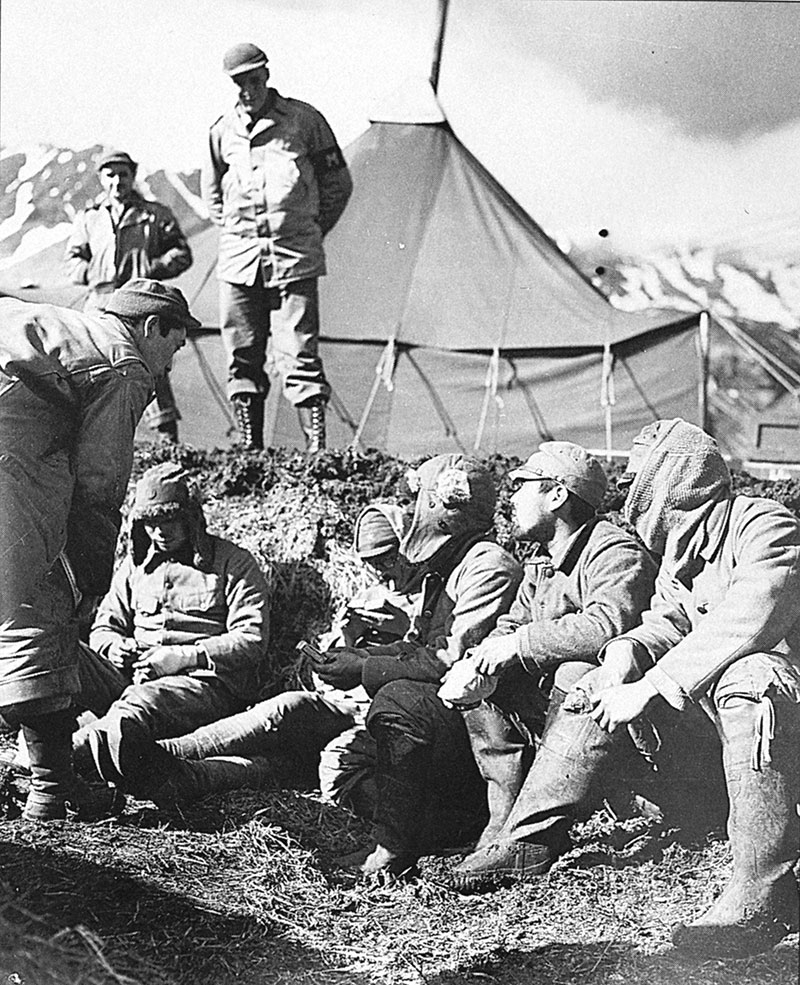

In the vanguard that halted Japan’s advance in the Aleutians and the Solomon Islands.

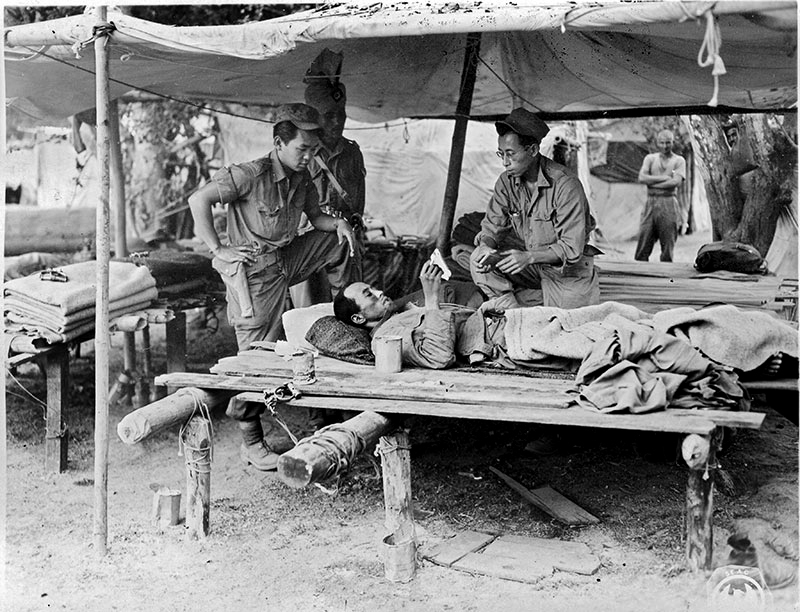

At intelligence facilities from Hawaiʻi to the newly created Pentagon, spending countless hours listening to Japanese radio communications, poring over documents for vital information, or questioning POWs.

Fighting with Merrill’s Marauders in the jungles of Burma, where they focused their language skills to overhear and intercept enemy communications.

With the Mars Task Force and Office of Strategic Services Detachment 101 in Burma, with the Allied Southeast Asia Translation and Interrogation Center in New Delhi, and in China with Nationalist and Communist forces, the OSS, and the Sino Translation and Interrogation Center.

In New Guinea, with Australian and American forces that engaged in bloody battles against a determined enemy.

With General Douglas MacArthur in Australia, the Southwest Pacific and the Philippines. They gathered vital intelligence, translated captured documents, and made other inroads into the Allies’ knowledge of Japanese military strategy.

With the Marine Corps and Navy’s island-hopping campaign through the Central Pacific.

Many an Allied unit thwarted an enemy attack with vital tactical intelligence gained by MIS linguists from prisoners and captured documents.

The enemy inadvertently helped: Japanese troops were not trained to resist interrogation; they were expected to win or die. Nor were they barred from keeping diaries and letters that, when captured, provided priceless information.

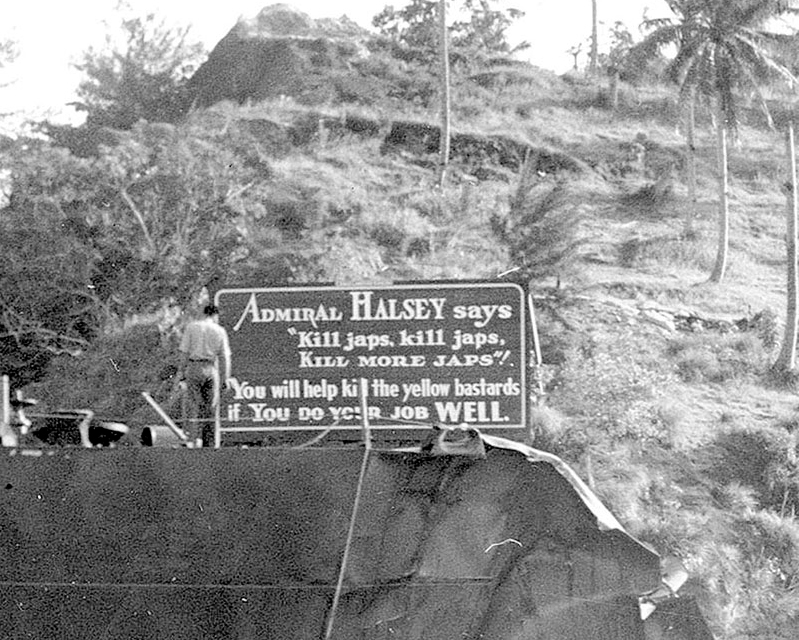

These intelligence efforts were often hampered by the tendency for frontline troops to take no Japanese prisoners, especially in the war’s early years. MIS language specialists sometimes resorted to offering rewards such as three bottles of Coca Cola or some ice cream to infantrymen who brought in live prisoners for questioning.

Meanwhile, in Minnesota, the MIS Language School had outgrown Camp Savage and moved to Fort Snelling.

Allies in the War Against Japan:

- United States

- United Kingdom (Fiji, the Straits Settlements, Tonga and other colonial forces)

- Republic of China

- Australia (including Territory of New Guinea)

- Commonwealth of the Philippines (United States protectorate)

- British India

- Netherlands (including Dutch East Indies colonial forces)

- Soviet Union

- New Zealand

- Canada

- Mexico

- Mongolia

- Free French Forces

- Guerrilla organizations: Chinese Red Army, Hukbalahap, Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, Manchurian Anti-Japanese Volunteer Armies, Korean Liberation Army and the Viet Minh

Next: Stemming the Tide